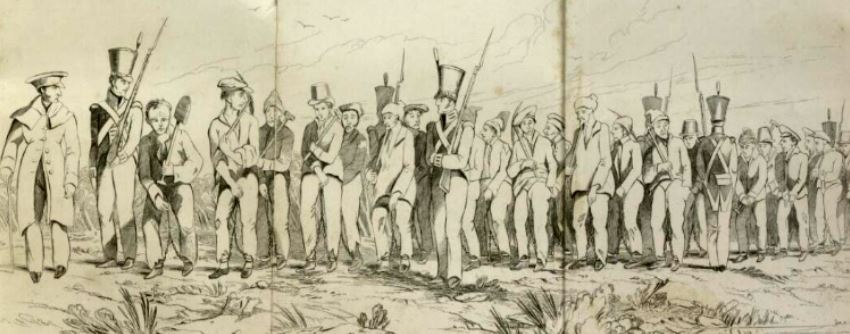

The ‘First Fleet’ , which arrived at Port Macquarie in April 1821, transported 60 convicts, along with 38 soldiers, civilian officials, two wives and four children. Two years later there were more than 1100 convicts, and by 1825 over 1500. By this time it became apparent to the colonial government that Port Macquarie could no longer effectively fulfill its original aim of being ‘a place of banishment’. The spread of settlement in New South Wales meant convict escapees could more easily reach outlying settlements and thereby effect a more ‘permanent’ escape. Norfolk Island presented a more isolated and desirable location to send the worst offenders; somewhere where escape was impossible.

By 1830 the transportation of convicts to Port Macquarie had virtually ceased and the district was opened up to free settlers. Convicts sent to Port Macquarie after this time were those considered incapable of working due to physical or mental incapacity. In 1840 the transportation of convicts from England to Australia effectively ended and the decision was made by the Colonial government in 1847 to dismantle the penal settlement and remove the remaining convicts to hospitals in Sydney and Liverpool.

Surveyor-General John Oxley sighted the Hastings River in 1818 and recommended it to Governor Macquarie as a sight for a future settlement. Only three years later three small ships sailed from Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) carrying soldiers and convicts to establish a penal settlement at the mouth of the Hastings River, at the place named Port Macquarie by Oxley in honour of the Governor of New South Wales, Lachlan Macquarie.

Surveyor-General John Oxley sighted the Hastings River in 1818 and recommended it to Governor Macquarie as a sight for a future settlement. Only three years later three small ships sailed from Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) carrying soldiers and convicts to establish a penal settlement at the mouth of the Hastings River, at the place named Port Macquarie by Oxley in honour of the Governor of New South Wales, Lachlan Macquarie.

The Port Macquarie penal settlement was intended as a place of secondary punishment for those convicts who had committed further crimes in the colony. It was considered far enough away from other settlements in the colony so that convicts would be discouraged from trying to escape.

To build this new settlement, instructions were given to select convicts with the required skills, and who had proved steady and reliable in their current work gangs. So among the first sixty convicts were three carpenters, two sawyers, one blacksmith, one tailor, two shoemakers, and a medical assistant, with the rest being labourers. Those selected to come were also promised a ticket-of-leave or a conditional pardon at the end of their sentence should they prove to be well behaved and perform good service.

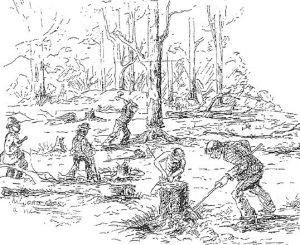

The first task of the new arrivals was to establish a temporary camp a short distance from where the permanent township was to be built. Bark huts were constructed for the convicts and tents were erected for the soldiers and civilians. Later huts were to be built for the military some 300 yards (270 metres) behind the huts for the convicts. Next on the list of required buildings were a provisions store, a guard house and a gaol.

The colonists carried six-months provisions with them from Sydney to sustain them until the settlement should become self sufficient in food. To this end some tracts of land was set aside near to the camp for the cultivation of wheat and maize. Convicts were also encouraged to cultivate their own gardens for the production of vegetables and other food crops.

The task now before Commandant Allman was to build more permanent structures to house the increasing number of new convict arrivals that would be transported to Port Macquarie over the next few years. The original camp, barely able to protect the population from the weather, was relocated to higher ground in August 1821.

The arrival of more tradesman, namely brickmakers, a bricklayer and a carpenter, facilitated the construction of new, more permanent, buildings. By September the convict tradesman and labourers were building new barracks for the soldiers, and by October 1821 the settlement boasted weatherboard huts able to house 400 convicts and soldiers, a house for the Commandant, barracks for the Convict Overseer and the Chief Constable, as well as provision store, a granary and a guard house.

In the six months since the arrival of the first three ships a substantial settlement had been carved out of the wilderness, ready to accept the secondary offenders and worst behaved convicts of the colony. However this promising start was not to last and it wasn’t long before alternative places of banishment were being considered.

So who were these convicts who volunteered to be transported to Port Macquarie? Unfortunately no definitive list exists that puts names to them. We do know that there were sixty convicts; and we do know some of the names, and further research is being done, some however will remain anonymous footnotes in the history of the European settlement at Port Macquarie.

Some research to date includes:

Roberts, D. A. Colonial gulag: the populating of the Port Macquarie penal settlement, 1821–1832

October 2017 History Australia 14 (4) 588-606

Smith, Clive. Port Macquarie’s First Convicts Port Macquarie Historical Society Inc.

General Muster of 1822 – Port Macquarie data extracted by PMHC Library

The rapid pace of development of the colony of New South Wales was to shape the future of the penal settlement at Port Macquarie. While initially selected as a ‘place of banishment’ for secondary offenders, it soon became clear to the military, and the government, that Port Macquarie was now too close to other settlements to remain a deterrent to escaping convicts. It was soon time to open the district up to free settlers.

From 1825 the first convicts began to be transferred to the new penal settlement at Moreton Bay (Brisbane) and also Norfolk Island. Governor Darling, who took office on 19th December 1825, was keen to accelerate the removal of prisoners from Port Macquarie and open the area to free settlers. Darling was also concerned about the ‘trivial’ nature of the crimes committed by some Port Macquarie convicts and wanted to ensure that only crimes of the worst kind resulted in banishment to a penal settlement outside of Sydney. Furthering his case for closure was the fact that Port Macquarie penal settlement was the most expensive to maintain of all establishments.

By December 1828 only 412 prisoners remained at Port Macquarie. On 26th November 1828, Sir George Murray, Secretary of State, authorized Governor Brisbane to de-commission the Port Macquarie penal settlement. In July 1830 Darling issued a proclamation declaring Port Macquarie open to settlers. The ‘worst’ of the prisoners were to be transferred to Norfolk Island and Moreton Bay. By the end of July 1830 there were approximately 32 prisoners left at the settlement who, with their wives and children, were to be assigned to free settlers.

In the years following a number of settlers selected property within the new town plan of Port Macquarie and in the surrounding districts. Major Archibald Innes gained much land at this time. Agriculture and timber getting were the main industries to occupy the new settlers and the Hastings River, navigable as far as the present site of Bains Bridge, provided a vital highway for commerce and trade.

The removal of the last of the convicts, and economic slumps, were to affect the prosperity of the district, and through the middle years of the 1800s Port Macquarie suffered a decline. Wauchope grew on the strength of the timber industry to become the main town of the district. Alfred Pountney, who founded the Port Macquarie News and Hastings River Advocate in 1882, described in an editorial how “the first thing that strikes a stranger is the dilapidated and faded nature of the town”. From convict beginnings Port Macquarie was to slumber for many years before slowly transforming into a place of recreation and retirement.

Few buildings remain from the early convict years of Port Macquarie, however the history of the period has been well researched with many books available through the Port Macquarie-Hastings Library, while the Port Macquarie Historical Museum and the Mid North Coast Maritime Museum both provide excellent displays that give life to those early years. There are also a number of historic maps that chart the development of the early settlement.